Walking with Markus of the Maasai

Article and photos by James

Michael Dorsey

|

|

|

Author at Markus' boma (a family compound in a Maasai village).

|

The view from my tent is a panorama of the Great Rift Valley, the immense rock wall in the distance rising slowly from the highlands of Manyara and creeping northward to terminate in the massive caldera of Ngorongoro Crater.

The weight of history on this land is a physical presence. Evidence of the earliest man keeps revealing itself to archeologists, with each find pushing back the number of years that my ancestors have tread where I now stand. I am less than 30 miles from the last nomadic clans of the Hadzabe, East Africa's Stone Age Bushmen, and one of three distinct genetic groups from which all of humanity is descended. The valley before me is literally the cradle of humanity.

The bomas of 300,000 Maasai surround me, filling the Manyara valley like so many brown mushrooms. Early morning cooking fires layer the valley with a low, flat mist pushed down by the lingering cool night air.

|

|

|

Camouflaged boma.

|

|

|

|

Maasai taking

cattle out to graze.

|

Markus Appears

A figure ambles uphill through the mist, robes billowing wraithlike in the morning chill. It is a Maasai from one of the bomas I drove past late last night; he is alone. Typically, at this time of the morning, the boys and young men escort the village cattle out to graze, so his presence suggests that he is beyond such menial labors. As he draws near, I see that his shuka is a deep magenta, and he carries an ebony walking stick that identifies him as an elder, a title of respect rather than age. He walks with the grace of one used to authority. His pace is slow and steady, pole pole, as they say here. He stops just downwind from my tent and, with a broad smile, addresses me in Swahili, the lingua franca of East Africa.

"Jambo Papa," he says, referring to my white hair.

“Jambo Papa,” he says, referring to

my white hair.

In Africa, I am almost always older than the most ancient man in the village. In this land, age commands respect as it does nowhere else. Papa is a standard greeting here for an elder of any race.

“I come to welcome you,” he adds in

heavily accented English.

I share my morning coffee with him as he squats in front of my tent in a local traditional way that my knees no longer allow me to do. His name is Markus, and he emphasizes that it is spelled with a "K." It is common in Africa for tribal people to adopt a Western name to eliminate their own from being butchered by English-speaking visitors.

Markus smiles broadly at me over our coffee, showing off the gap where his front tooth has been removed. As is the case quite often with first white contact, early British and German colonists in East Africa in the 19th century brought their homegrown diseases with them, unknowingly inflicting them on the local inhabitants who had no immunity to such outside terrors. Among the most rampant was lockjaw, a serious bacterial tetanus that can freeze muscle control and eventually lead to death. The Maasai were among many tribes appalled by the concept of starving to death while being unable to open one's mouth to eat. The result was the removal of one or two prominent front teeth to facilitate the intake of nourishment. The practice continues to this day among the more remote tribal clans.

|

|

|

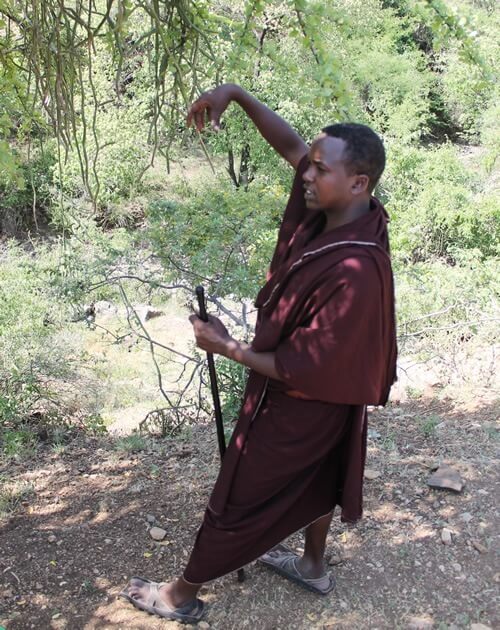

Markus explaining

medicines.

|

After our coffee, Markus stands and walks slowly up the hill behind my camp. The Maasai rarely waste unnecessary words. A simple gesture is enough to beckon, so I follow him silently. Above the morning clouds, we reach a flatland full of thorny acacia trees. I tag along as Markus temporarily disappears into a thicket. The interior reveals an obvious campsite. We sit on a fallen tree trunk to examine the bony remnants of previous hunts. The trunk is notched to show the number of days the Moran, the newly initiated warriors, have occupied their base camp. It is where they come to eat meat privately, with no women allowed, a testosterone-fueled man cave in the ancient forest. It is a rare honor that Markus has revealed the location to an outsider.

|

|

|

Author and Markus

sitting peacefully on a tree trunk at a warrior camp.

|

Markus starts in on a pantomime of a hunt that soon has me laughing aloud. He lifts his shuka to proudly reveal all the scars of being a Maasai warrior.

Before a Maasai boy is considered a man, he must hunt a lion with a spear and shield. He does not have to kill the lion but must participate in the hunt. The origins of the tradition are long forgotten. Lion hunting has officially been banned in much of East Africa because of terrible losses due to poachers, but it still occurs in remote areas.

These days, the Maasai typically hunt a lion by surrounding it with warriors who slowly advance, tightening the circle until it is so narrow that the lion has no choice but to attack to fight its way out. The warrior the lion attacks will fall to the ground, cover himself with his shield, and hope his brother warriors will slay the great beast before it kills him. The bravest hunters will attempt to grab the lion's tail while this is going on, conveying an immense face to the holder.

|

|

|

How the Maasai hunt a lion.

|

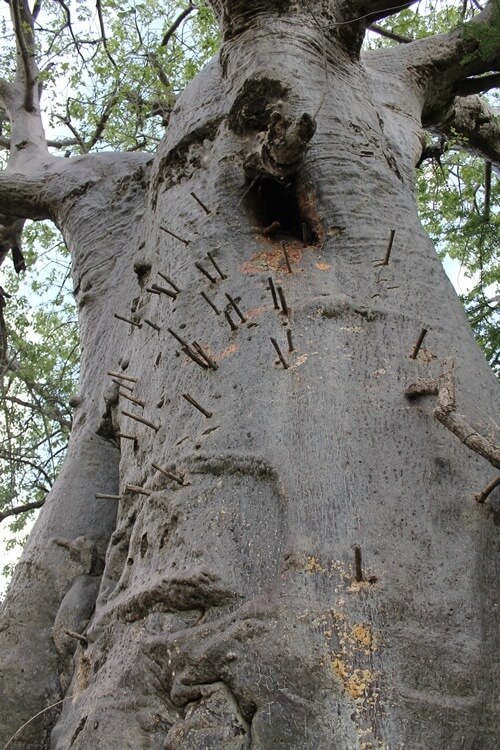

We continue our walk up the hill, Markus padding silently in his rubber sandals made from old truck tires, the Maasai equivalent of Crocs, until we stand on a steep slope. Our necks crane backward to take in the towering immensity of the largest baobab tree I have ever seen, with its spreading boughs most likely home to hundreds of varied creatures. Numerous small branches have been hammered into the side of the baobob tree in an alternating pattern. Markus uses the branches to begin climbing. Twenty feet above me, he pointed out a giant beehive I would never have noticed. Sitting on a massive branch, Markus tells me how the Maasai trail a small black and white bird called a honeyguide that brings them to such trees. He explains how they make a torch to smoke the bees out to steal the honey, a rare delicacy in these parts.

|

|

|

The honey tree.

|

As we retreat down the hill, Markus points out a dozen different plants and bushes that provide the Maasai with medicine, meticulously explaining how each is harvested and utilized. His movements have a grace, a flow that expresses harmony with his surroundings. The Maasai believe that ancestors watch over them as part of the land, and Markus appears as an organic part of the whole.

Suddenly, Markus stops to dig up a tiny green plant, knocking the dirt from its roots. He holds it to my stomach and moves it around in a circle. "What does this do?" I ask. Markus laughs, "Makes you not so fat!" referring to my Western girth. He then giggles as he makes a sign with his hands of his tiny waist compared to my rather sizeable Caucasian midsection. The wise man is also full of humor.

We have walked for over three hours, and when we are almost back at my tent, he stops and stands silently, taking in the panoramic view. He is smiling, but then he has been smiling all day. I stand next to him and whisper, "Enkai," referring to the Maasai equivalent of a deity that is beyond the comprehension of most Western city dwellers. Enkai encompasses all of nature if I have heard and understood correctly. A more detailed explanation of the meaning is beyond my abilities and probably beyond understanding by anyone not born a Maasai. "Yes, Enkai," he quietly says with great satisfaction.

I invited him to sit for coffee again when I arrived at my tent, but he politely refused. I extend my hand for a farewell shake, and he reaches inside his robe to produce a small gourd meticulously decorated with beadwork, a hallmark of Maasai culture. The gourd is half the size of a tennis ball and has a cork stopper in the top hole. It is a snuff carrier, one of the only true vices of Maasai men who seem addicted to it. The gourd is the sort of gift only given to a friend. He places it in my palm and closes my fingers around it. With that, he turns to walk back down the hill, disappearing into the mist as mysteriously as he first appeared.

I never asked him why he came to see me or spent most of the day sharing esoteric knowledge. Perhaps he was curious about this lone traveler in his land when my kind generally arrived in large groups of safari vehicles with cameras clicking. Maybe he sensed that I was different and would understand in a way most visitors never can. I like to think that I do.

If I have learned one crucial lesson from my travels across Africa, it is that tribal people inhabit a separate reality from me. There is no distinction between the material and spiritual worlds; they pass between them seamlessly. Markus had just offered me a taste of his worlds, a gift beyond my expectations.

|

|

|

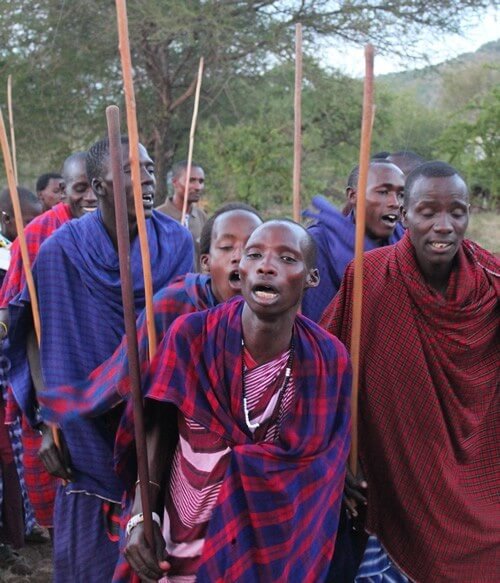

Maasai singing and

dancing.

|

Whatever his reasons for seeking me out, I would rather not know. I prefer to accept his hospitality at face value, appreciative of the rare days that occasionally come only to those who wander far off the beaten path.

I return to that day in my thoughts quite often. Most recently, while driving through the immense city in which I live. I was pulling into a drive-in hamburger stand when I remembered Markus rubbing that plant against my stomach and laughing while he told me it was to "Make you not so fat."

I pulled back into traffic without a hamburger but with a smile and kept driving.

James Michael Dorsey is an explorer, award-winning author, photographer, and lecturer. He has traveled extensively in 45 countries, mostly far off the beaten path. His primary pursuit is visiting remote tribal cultures in Asia and Africa.

|