How to Manage Your Money Safely on the Road in Latin America

A Realistic Guide by a Long-Time Expat

Article and photos by Ted Campbell

|

|

The essentials for managing your money in Latin America.

|

Her eyes fill with tears. “What am I going to do?”

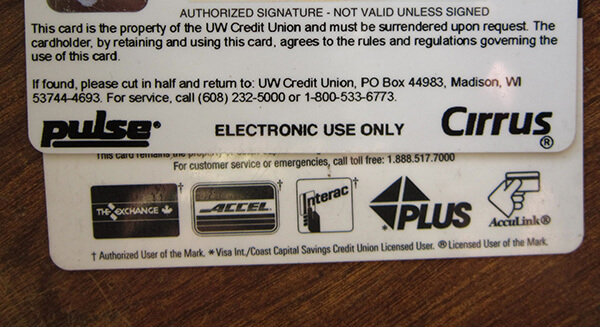

I take my U.S. debit card out of my wallet. I show her the little symbols on the bottom — Cirrus and Pulse. I take out my Canadian card — The Exchange, Accel, Interac, Plus, and Acculink.

“See how yours doesn’t have any,” I say.

“But it’s a Visa!”

What can I say? The card doesn’t work. You can’t argue with an ATM machine.

We’re standing outside our third ATM in 30 minutes. Merida is hot in the early afternoon. Hours from the beaches of Cancun and Playa del Carmen, the capital of Mexico’s Yucatan state is surrounded by deep green jungle. Sweat beads on the foreheads of people passing on the narrow, crowded sidewalk. Club hits blast from discount clothing stores, somehow making the day even hotter.

“Well, I have another card back at the hostel. It might have those symbols,” she says.

We go back. Her card has lots of symbols. “Remember, find an ATM with the same symbol,” I say. “Do you want me to go with you?”

“No, I’ll be fine.”

Five minutes later she bursts into the room, tears flowing. “The machine ate my card!”

We run downstairs to the ATM in the OXXO convenience store next door. Sure enough, none of the magic symbols from the backs of our cards are pasted on it. It isn’t even an international ATM, but for a local Mexican bank. I see no point in repeating what I have been saying all afternoon. I give her a hug and tell her not to worry.

|

|

It is very important to know how to read the symbols on your ATM card when you travel in Latin America.

|

“I just want to go back to England,” she says.

A Common Money Problem

When I meet travelers on the road who are having money problems, it’s rarely because they ran out of money or got robbed. Usually they don’t understand the different kinds of ATMs and debit cards. Perhaps they don’t know their bank’s policies. Perhaps they have been ripped off changing money on the street or while crossing borders.

Quite simply, they didn’t prepare. They assumed that something they took for granted back home, money and banking, would be the same overseas.

Understand ATMs

Debit cards are essential for travel. ATMs give decent exchange rates and are usually easy to find. But you must understand them first.

As I told my unfortunate friend, the symbols on the back of your debit card mean everything. You have to match a symbol on your card (Cirrus, Pulse, etc.) with a symbol on the ATM you want to use. These symbols show that the ATM is part of a network to which your bank has access.

Basically, there are two kinds of ATMs, local and international. Local ATMs will have no symbols. International ones will have lots of them.

But for some reason, a Visa or MasterCard symbol on both your card and the ATM doesn’t always guarantee that the card will work. You can use these cards as credit cards in restaurants and hotels, but that’s a bad habit to get into. The fees and surcharges can get away from you, and there’s a very real possibility that someone can steal your number. I try to never use my debit card as a credit card.

Understand Your Bank

Banks are a strange business. You might have to do some research, but you will find important differences between them. Know how much you will be charged for international withdrawals. For example, my U.S. bank takes 1%, while my Canadian bank charges $4 per use.

Learn your bank’s policies. How can you transfer money? Online? Are there fees? Remember to be extra careful if using public computers. Change your password often.

If your existing debit card doesn’t have lots of those magic symbols, get a new card. If your bank can’t offer you one or wants to charge you for it, then get a new bank. If you live in the U.S. or Canada, I recommend a credit union.

Always Have Backups when Traveling

Travel with several cards. You never know when you’ll lose one. I’ll never forget the day in La Paz, Bolivia when I strolled away from the ATM, went two blocks and realized I had left the card in the machine. I ran back and it was gone.

I had a backup card, but it didn’t work. So I waited two weeks for the new card to come, running up tabs in the hotel and my favorite bar up the street. But my bank (a credit union) mailed me the card relatively quickly and didn’t charge me for it.

Now I travel with many cards, from three different countries even. But the easiest way is to just open a second or third checking account in the same bank and get a card for each. If it isn’t free, change banks.

Communicating with your bank before your trip is important. It won’t take long — a quick visit, phone call or email should do. Inform them you will be traveling abroad. This is important because once they see withdrawals from faraway lands they may lock out your card as part of a security policy. Unlocking your card will involve being put on hold during long distance phone calls, at the very least.

Ask your bank carefully about their withdrawal policies and fees. You will get an idea during this exchange how they would treat you if you had a problem. No reply to the email? Lost in voicemail, or stuck on hold too long? Find a new bank.

A PayPal account is very useful as well, especially if you pay for anything online, like airline tickets. Get their free MasterCard debit card as a backup card. It's easy to transfer money from your checking account to PayPal if your primary debit card is lost, stolen or locked out by the bank.

If you use a credit card — not a debit card that works as a credit card — be sure to learn their policies for international transactions and currency exchange. Withdrawing cash from some credit card accounts can cost 25%+ interest from the day you take out the money until you pay the outstanding balance in full.

When purchasing anything with a credit card, ask that you be billed in the currency of the country you're visiting. Say "no" if asked to be billed in U.S. dollars. The merchant's exchange rate will be exorbitant; the credit card's will be reasonable.

When you get home, examine your credit card bills and bank statements because currency translation percentage rates and fees errors are common, especially if you bank with a smaller, regional or community bank.

If you have a smartphone with a camera, download an "expense report" app that allows you to enter expenses in most foreign currencies. Photograph the receipts from your trip. When you get home the reports and receipts will settle any disagreement you might have with your credit card or bank.

Cash Money

I can’t speak for the whole world, but where I live and travel in Mexico and Central America, the U.S. dollar is king. You will always get better exchange rates at borders, and dollars can be exchanged almost everywhere.

I usually travel with between $100-200 USD in 20-dollar bills. I try not to use them unless I have no other choice. Trekking to some crazy out-of-the-way place and finding out that they don’t have an ATM isn’t much fun if you want to stay awhile.

If it isn’t the U.S. dollar, then I’m sure most parts of the world have some other most-desired currency, like Euros or Yuan. Find out what it is beforehand and bring some.

Checking exchange rates is easy. Do it online with using your favorite search engine. An easy website to use is coinmill.com. Compare the rate over time while abroad to see how it fluctuates.

If international finance interests you, open a foreign account and send money back and forth. You can make good money doing this, but it will have to be enough to cover the fees for the money transfers.

Traveling Safely

Now you have a stack of debit cards and some tasty U.S. dollars. Sounds a little dangerous?

Getting robbed is always possible while traveling. The odds go up and down in certain parts of the world, but if you are staying in hostels, in a room full of bunk beds, then you should be very careful.

My first line of defense is a thin money belt that fits under my pants. Some people — especially girls — use a small pouch that hangs around their neck.

You keep the essentials here — passport, debit cards, and any backup cash (like U.S. dollars) or local currency you won’t be spending that day.

I don’t carry this at all times, only when I’m traveling between places. When I have a place to stay, I leave it in my room. Some travelers use the safe deposit box of a hotel. Even cheap places might have a safe under the front desk. Just be careful when you ask — don’t imply you are carrying a treasure!

I have a small corner of my backpack to hide it in. Or you can wrap it up in old clothes and stuff it down to the bottom. Hollow out a book and tie it with a rubber band. You get the idea. But only hide stuff in your backpack when you leave the backpack in your room. While taking buses or other public transportation, you want that pouch to be out of sight and touching your skin.

That reminds me — put your cash and passport in a Ziploc bag to keep them from getting drenched with sweat on a hot bus in a hot country.

Prepare for a Robbery

One more thing: there’s no point in having all this money hidden if you have nothing else to give a robber. You will end up yanking out the money belt to appease him.

When I’m in dangerous places, I carry money on me in three places. The essentials and whatever I’m sure I won’t need is in the money belt. Whatever I will use that day is in small bills in my front pocket, in a wallet or not. And whatever backup cash I might need, I stuff into my socks.

Sounds paranoid? Think about what it’s like getting robbed at knifepoint. What does that robber want? He wants a foreigner’s wallet stuffed with bills (even if they are all small bills) and a quick getaway. Make sure that you can provide it.

Currency Exchange at Border Crossings

A day or two before you cross the border, go online and check exchange rates. For example, last summer when I crossed from Guatemala to Mexico, I found that the rate was 1.65. This means that 100 Guatemalan quetzales will get you 165 Mexican pesos. But I’m bad with math, so I wrote down how much the total in quetzales I would most likely be exchanging is worth in pesos. I did the same for U.S. dollars.

Speaking the local language will help, but it isn’t essential. Carry your cheat sheet and a pen, or think about getting a small calculator. Borders are full of moneychangers, and if you sound like you know what you are talking about you will get a good exchange rate, sometimes even better than the official one. If you are clueless, you will get ripped off, big time.

Again, this is where U.S. (or some other) money might come in handy. If you are getting bad rates for local currency (especially if you will be going back to the country and don’t mind carrying it), then you might get a better rate for dollars or another currency.

Crossing borders can be intimidating. Research as much as you can — not only exchange rates but also what to expect in terms of visa requirements, which are subject to change. Know where, how far apart, and how far from the next bus station the immigration offices are.

Many people take shuttles across borders with big groups of tourists. The idea is to save time and money, but in my experience they are expensive and sometimes very slow, especially in the morning when they drive all over town to everyone’s hotel.

Also, the few times I’ve done this I’ve seen rip-offs. At the Guatemalan/Mexican border on the road between Tikal and Palenque, the group was warned several times on the way about the Guatemalan exit fee. They all lined up to get their stamp, money in hand.

I knew this wasn’t true, so I asked for a receipt. I knew they couldn’t give me one. They saw all the other Guatemalan stamps in my passport and just waved me on.

I don’t suggest you try to make a stand against a suspected rip-off. Just quietly ask for a receipt.

Later on the same trip our van was stopped in Mexico. Officials asked us for a fee of about 80 cents. A couple refused. I asked for a receipt and got it — a fee for the national park/nature reserve we were passing through.

The angry couple refused a legit national park fee but had paid the bogus border-crossing fee. It was quite embarrassing to wait in the hot, crowded passenger van for ten minutes until they finally relented and paid.

The Last Word on Money and Traveling

Time is money. Money is power. Money is the

root of all evil. And so forth...

Money is also your ticket to a great trip in a far-off part of the world. Or it can be a source of frustration and heartbreak, like what happened to my friend in Merida.

She was fine. The guy she was traveling with agreed to lend her money until they reached Cancun, where she would meet her sister.

I pictured them running around town, putting cards with no magic symbols in every ATM they found. Had she learned her lesson? Somehow I doubted it. Some people can be strange when it comes to dealing with money — they seem to not want to think about it, to understand it. They choose to have unprotected ATM use and assume that everything will be all right.

Sometimes it isn’t. With money and traveling, ignorance is anything but bliss.

|

Ted Campbell is a freelance writer, Spanish-English translator, and university teacher living in Mexico.

He has written two guidebooks (ebooks) about Mexico, one for Cancun and the Mayan Riviera and another for San Cristobal de las Casas and Palenque in Chiapas, both also available at Amazon.com or on his website.

For stories of adventure, culture, music, food, and mountain biking, check out his blog No Hay Bronca.

To read his many articles written for TransitionsAbroad.com, see Ted Campbell's bio page.

|

|