Life and Death in Tana Toraja, Indonesia

Article and photos by Chris Dunham

|

|

Baby Grave Tree in Tana Toraja, Indonesia

|

“We bury the babies in this tree so the wind can waft away their souls,” explained Stefan, our local guide, as we stared at the baby grave tree in Kembira, Sulawesi. Its trunk was patch-worked with little niches, each the poignant final resting place of a baby dead before cutting its first tooth. Death and burial, ruled by a complex set of long-established customs, are an ever-present feature of life in Tana Toraja, an isolated, predominantly animist community in the center of this little-known, octopus-shaped island in Eastern Indonesia.

Arriving in Tana Toraja was like stumbling upon a lost valley. The community is hidden behind a steep wall of mountains and was unknown to Europeans until the 20th century. At first glance, its peaceful, pastoral landscape could be taken for Austria: green fields dotted with steep-roofed houses and animals grazing against a backdrop of misty mountains. On closer inspection, you see buffaloes, not cows, wallowing in lush rice fields and houses that are not exactly your typical Alpine chalets. They are called “tongkonan, " lavishly carved and painted black, red, and orange in intricate patterns. Their curved roofs soar skywards, symbolizing the prows of the ships that carried distant ancestors to the island long ago. They can be neither bought nor sold but passed from generation to generation. The older ones proudly display rows of buffalo horns. Why? I found out as soon as I attended my first funeral.

|

|

Houses in Tana Toraja.

|

Funerals are, without a doubt, the main event on the Torajan social calendar. They can last up to a week, and no expense is spared. Local people are proud to welcome outsiders to their family funerals. On my third day in this mysterious land, I found myself just outside the small market town of Rantepao, following a procession of female mourners. The women carried a long train of red cloth above their heads and were led by the next-of-kin — a gentle-looking, slim young woman. She was dressed in red, the color of death in Sulawesi, with a brightly-colored beaded yoke across her shoulders and a matching sash around her waist.

|

|

A chief mourner at a funeral ceremony in Tana Toraja.

|

|

|

Funeral dancers in Tana Toraja.

|

At the head of the procession, the coffin bounced and jostled along in an atmosphere that would make an Irish wake seem positively somber. Later, I watched, entranced, as the men, slightly merry by then from palm wine, or “tuak,” joined hands to form a circle and chanted the deceased's life story while swaying in slow rotation. This circle of life paused as each man sang his own short, personal tribute and was then joined by the rest in a kind of group chorus. Despite my Western cynicism, I found it surprisingly moving.

I could have done with a few stiff tuaks myself later when it was time for the sacrifices. A fierce-looking individual wielding a machete stepped forward from the crowd and went to work. He certainly looked the part with his patterned bandanna and his droopy mustache. I knew what was coming. The buffalo tied to a post in the center of the muddy clearing had been struggling helplessly for a while. It seemed to know, too. The machete swung, and the beast dropped to its knees, twitching as blood gushed from the gaping hole in its throat. Once all life had drained from it, its flesh was swiftly chopped into pieces and shared amongst the guests.

The sacrifices may seem brutal to European eyes, but to Torajans, they are a simple demonstration of social prestige. Hence, the buffalo horns, accumulated over generations, embellish the older tongkonans, bearing witness to years of family status. These important social events can only occur once the family has saved enough money for the considerable expense. The high cost of buffaloes, the status symbol of Torajan society, and catering for numerous family members who return from far and wide to attend means it can be anything up to three years before it finally goes ahead. During this time, Stefan explained, the deceased continues to “live” in the family home, considered sick but still part of family life. When the big day finally arrives, all tears have been shed, and the only wish is to have a good send-off.

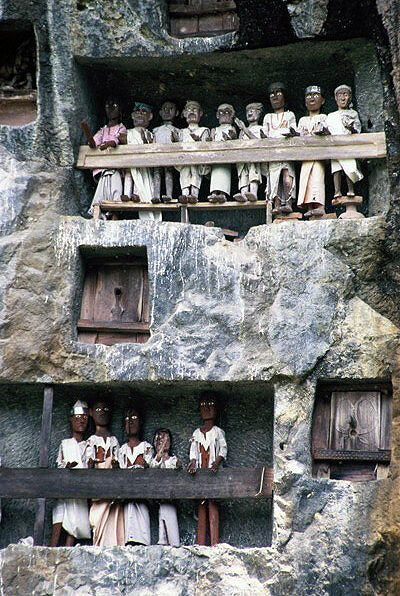

Had the babies at Kembira lived longer, they too would have been honored in this way, eventually joining the “tau-tau.” These are haunting, life-sized wooden effigies of the dead perched high on the cliffs. They stand in rows in galleries cut into the rock at a height that reflects their social status when alive. They stare across the rice fields like passive opera-goers, watching a performance from their boxes. Torajans believe they protect their villages from evil. I saw them at Lemo, to the south, some touchingly adorned with what, in life, had been a favorite garment or piece of jewelry. Apparently, tradition dictates that the installation of a new figure must be accompanied by the sacrifice of 29 buffaloes and 59 pigs, a gruesome scene I doubt I could stomach.

|

|

Tau-tau life size wooden effigies perched on cliffs.

|

|

|

Pigs sacrificed as part of the ritual.

|

Although many of the sights of Tana Toraja might seem rather macabre — as well as attending funerals, you can visit ancient tombs full of dusty, boat-shaped coffins, spilling bones, and skulls — there is no doubt that they give unique insights into this fascinating ethnic group who practice a unique form of animism.

|

|

Human skulls from ancient tombs.

|

Another quite different attraction is the spectacularly beautiful countryside, where the vast, unpolluted skies are reflected in the endless, glistening rice paddies. In Torajan culture, rice is almost mystical in importance. You sense it as you watch people busy in the fields, engrossed in the timeless cycle of planting, harvesting, and drying it — all by hand — before storing it in rice barns, a scaled-down version of the tongkonans and every bit as elaborate.

|

|

A rice barn in Tana Toraja.

|

As my stay among these hospitable people drew to an end, I pondered what I had learned about their magical philosophy, their constant efforts to balance the opposing forces of life and death, their rituals revering what is from the east and therefore "life-giving," while fearing what comes from the west and is consequently "death-causing." As a Western visitor, I was glad I was not included in that category and had been allowed to be a privileged observer of the sacred ritual expression of such unique spiritual beliefs.

|