Travels in Fiji: Before We Lived Barefoot

Article and photos by Susan C. Bonetto

|

|

Fijians preparing for a traditional dance ceremony.

|

I sometimes daydream of Fiji, though I lived there for many years, and memories most often connect to our first trip to the South Pacific. Our friends, Mimo, a French-Algerian, and Rigel, a Japanese-American, were a carefree San Francisco couple who had recently visited Fiji, and they recommended that we spend a little time on the islands. Without significant encouragement beyond gathering the basic facts that it was a mild tropical climate with temperate people, we booked a two-week trip that would change our lives forever.

No Reservations

We spent our initial week along the Coral Coast at the Waratah Lodge. We mostly followed Rigel’s travel recommendations. She had advised that it was affordable in an agreeable area near Sigatoka, one of the larger "cities" in Fiji. Most importantly, the lodge was right across the street from the beach.

We usually ad-libbed our travel arrangements, but as it was a lengthy trip, we wanted to ensure a comfortable entry, so we called the lodge a few weeks in advance to make a one-week booking. Three weeks later, we arrived at the small inn with six bungalows to learn that Oscar and Susan Bonetto had no reservation.

“Ani must have forgotten to write it in the book when you called,” breathed the young Melanesian woman with a fire-red hibiscus flower in her hair. She told us her name was Mere and we stood without speaking, pondering our shared next steps.

I began to detail our intricate connection attempts. “Beginning four weeks ago, we made countless unanswered calls. At first, the phone seemed to ring and ring and we weren’t sure if it rang or was busy or disconnected because phones ring differently in the U.S. But we kept calling at different hours and the woman named Ani answered with a lovely singsong 'Bula.' I asked Ani if she needed a credit card to confirm the reservation but she said 'No' and doubly assured me that everything was set.”

I was talking too much for Mere or Fiji, and Oscar recognized this before I came up for air. He stepped into my chronicle and gently posed the vital question. “Might there be a bungalow available anyway?”

As worry-prone Westerners, we’d started to fret a bit. Yet, Mere responded to Oscar’s question with something soothing, like a melodic little rhyme, “Sega na lega.” We soon learned that this boils down to "no worries" and is more or less Fiji’s mantra, applied to predicaments large and small 99% of the time. Mere informed us that we could have a bungalow for three nights, following which we would have to leave to make room for guests who had bookings. Ani seemed to have remembered to write down their other reservations.

As luck would have it, three nights on the oh-so-boring Coral Coast was enough for us. Though a fine place for the less active that enjoy lying poolside sucking on pineapple-flavored drinks, we prefer to adventure through our vacations. Vigilantly picking our way through jutting pieces of coral in ankle to knee-deep water was different from our idea of beachside fun in the sun. We could snorkel only in high tide as low tide meant scraped bellies until you swam far enough to find deep water. And those deeper waters often had dangerous undercurrents, whose reports of grabbing an occasional unsuspecting tourist floated down the shore, passing from one uninspired vacationer to another.

So, we idled away the days, the highlights of this interlude being visits to the colorful Sigatoka fruit and vegetable market, meeting a local man who invited us to his village for Sunday church, followed by a lunch with the entire community of serene, minimalist islanders, and the tranquility of naps under an exotic mosquito net with fans above stirring the air just after a bit of afternoon delight.

|

|

Traditional Fijian Bure (gathering place).

|

Hitchhiking to Suva

When these days ended, we gamely packed our two small bags. We hitched a ride to Suva, Fiji’s capital city, a few hours’ drive from Sigatoka. Rigel’s travel itinerary included spending another week split between Levuka, the historic capitol city of Fiji on the island of Ovalau, and Leleuvia, a pocket-sized backpacker island resort that was one day to become our home.

Hitchhiking in Fiji is safe and accessible once you know how.

As we departed, the Waratah staff was on hand to send us off, calling out a profusion of "Moce Madas" ("Good-Bye — See you soon"). We stood on the main road in front of the lodge, and Oscar threw his arm out at a 90-degree angle from his body with his thumb facing skyward.

The Fijians exploded in united laughter while the gardener’s little boy started throwing his arms out and thumbs up in the same way, then gleefully grabbed his belly. His father hurried towards us and, without saying a word, demonstrated how Fiji-style hitchhiking was done. Forget about holding your arm out for minutes and dispensing with your thumb. See a car coming and, as it nears, hold your arm down at a 30-degree angle, with your hand facing downward, and flutter up and down ever so slightly. Chances are good that the first vehicle will stop for you, even if it is a farm truck with no more than a corner vacancy in its dusty bed.

|

|

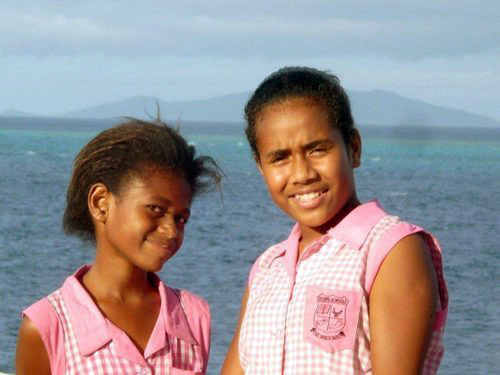

Fijian girls on the way to school.

|

The Cane Knife

And so we hitchhiked to Suva, but I gave a bit of pause when we entered the back of the second car of the day. Our new acquaintance was a local resident of few words. Sitting in his driver’s seat, he appeared tall and sinewy, with milk chocolate skin. We cheerfully introduced ourselves, and he reciprocated with a solitary reply, saying his name, Jone, offering no additional communication. Rather than attempting conversation, I leaned down to arrange my backpack on the floor. I found that my feet happened to be stepping on a serious knife, which was placed between the floorboard and mat. It had to be at least two feet in length. I did an unintentional double-take. I nudged Oscar with my foot, hoping, maybe, he would find an easy way out of the moving vehicle before we became part of a serial killer driver’s memoirs. But, he seemed unaffected and, under his breath, murmured that it was a cane knife as though this might clarify and assuage any worries I had. “Of course, a cane knife,” one side of my brain said to the other. I also tried out an unspoken “Sega na lega” in my mind, but it didn’t work. I didn’t have a measurement parallel for this situation and spent the next 20 minutes in a tense state of anticipation.

We’d now passed my acceptable limits of silence amongst people, even strangers, journeying together in an auto when, in the middle of nowhere, Jone slowed and, then, stopped the car. He briefly glanced over his shoulder towards Oscar with a simple invitation, “We have a drink.” Twisting my head back and forth, I searched the bush for a tavern while he leaned over the seat and picked up the knife. With a weapon in hand, he stepped out of the car and walked into a grassy, dense area. Meekly, we followed. He seemed to be searching the ground, casting about for just the right spot to dump our bodies. All of a sudden, he picked up a coconut. Holding it deftly in one hand, he launched into chopping all around the top, rotating the coconut after each hack. Within a minute, he proffered his coconut to me, and I slurped juice from the fresh hewn hole in the top, comprehending that this wasn’t my last meal and summarily proud to be acclimatizing to unusual customs. Another Fiji lesson learned. Apparently, most islanders travel with their cane knives — you never know when you might be thirsty and want to stop, walk into the bush to find a coconut to drink or chop up some firewood to carry home for cooking.

Onwards to Ovalau

Consequently, I lived to tell our ominous cane knife story, and we arrived in Suva on time to catch the once-daily bus to the Ovalau ferry. As one does in Fiji, we asked the first man we passed on the street where the ticket agency for the bus and ferryboat to Ovalau might be. “I’ll take you there,” he indicated, “but you won’t be able to go today.” We had already discovered that the locals are men and women of few words, but this short exchange left us baffled. “ Why can’t we go?” I asked George, our new friend and guide, but he took my hand and said, “Come, we go.”

Arriving at the ticket office only a block away, we immediately realized why we couldn’t go. Unbeknownst to us, the annual National Methodist Conference was in full force. More than a dozen buses and minivans filled with God’s devotees were ready to depart for the ferry that would transport them to Levuka, this year’s host site. Since spending time in the capital city did not fit our image of a tropical vacation, we decided to press on. Nevertheless, as George predicted, the ferry agent denied us passage despite our good-natured smiles and pleas. We started walking away from the office, unsure of our next move, when George approached us and offered advice. “Just go to a ferry bus without a ticket and they will take you.” George took us to meet one of the bus drivers, and we implored him to take us to the ship.

Soon, some of the locals on the bus began yelling out good-heartedly in their native tongue to let us on the bus. The bus driver shook his head and mumbled that we would not be allowed on the boat but ended with, “It’s up to you.” We could ride the bus to the ferry landing to gain access to the boat there. With a sense of triumph, we squeezed onto the overcrowded bus and squatted in the aisle, smiling at dozens of cheery brown faces as they beamed back at us. One and then another made direct eye contact, taking turns asking us the fundamental life questions — "What are your names?" "Where are you from?" "How old are you?" "Are you married?’ and ‘How many kids do you have?’ The Methodists were a spirited clan — chattering amongst themselves in Fijian after each of our answers. We reciprocated their directness and provided unabridged answers to their questions as we jostled our way to the landing, an hour’s drive from Suva.

Once again, we were denied passage at the ferry entrance due to facts that hadn’t changed — they were full, and we had no tickets. By now, the clan had adopted us, and the congregation joined our entreaty. After many warm-hearted Christian natives called out numerous times to allow us on board, God’s will appeared to be done, and we traveled to Ovalau aboard a ship overflowing with his servants.

Levuka

|

|

Levuka here seen from the sea.

|

Upon arrival in Ovalau, we learned that, from the boat landing, we were now about a forty-five-minute drive over an unpaved, rutted, and often flooded road from the only town on the island, Levuka, which was our destination. Once again stuck — there was no transportation to Levuka and no available rooms to stay, according to our light-hearted, spiritual friends, all of whom planned to stay in villages on mats no thicker than a sheaf of paper. But, one man yelled out to us Fiji’s overused slogan, “Sega na lega” followed by “Jump into the back of any truck and, if it doesn’t go all the way to Levuka, you will be welcome to sleep on the floor in any village we pass.” Such luck!

It was now past 7 p.m., and darkness settled in as we bumped and journeyed towards Levuka. Though tourist guides discuss it as an essential destination in Fiji, Levuka is a fishy-smelling, one-lane, Wild Wild West town from days of old. The main road, Beach Street, runs along — what else — the beach. At the same time, the other side is host to interconnecting ancient dilapidated shops and Chinese restaurants. In a few days, when less depleted, I would find the entire postcard passageway quaint, but at this very moment, it felt one hundred years distant from me.

Still following Mimo and Rigel’s directions, we headed for The Old Capital Inn. I asked for and found Simon — a "poofta," Fiji’s term for feminine gay men, who "Oi lei’d!" around us — another favorite Fijian expression used much like "Oh My!" — apologizing that they had no vacancies. In the sweetest voice, he explained the convention as though we could have arrived on the island without being aware. Simon directed us to check down the street at The Royal Hotel with a gentle “Come back and you can sleep on the floor in my room if they have nothing available.” Yet, another tempting accommodation offer.

|

|

The Royal Hotel in Ovalau, Fiji — the oldest hotel in the South Pacific.

|

In Search of a Room

Weary but not quite ready to sleep on the floor or with a man we‘d just met, we trudged a few blocks further and arrived at the oldest hotel in the South Pacific. At the reception counter, Oscar started speaking English like a Fijian. He said, “Please, is there a room here?” the elderly woman clucked her tongue and paused, glancing at the clock on the wall as though seeking its response. The clock remained silent as she turned back to Oscar and advised that as it was now nearing 9 p.m., we could have their last room that had been reserved for a honeymoon couple who hadn’t arrived that afternoon. We grabbed the key and hurried up the rickety wooden stairs, hoping the newlyweds had been turned away by the same ticket agent in Suva and wouldn’t show up anytime soon.

Our room was a set out of Tales of the South Pacific. Its walls were made of clapboard, and it contained a simple wooden chair, a double bed covered in old sheets with a faded floral pattern, and a mosquito net. We jumped into our tiny shower one after the other, washed off some travel dust under a mere drizzle of cool water, and fell into bed exhausted but satisfied. We were sound asleep within seconds.

Celestial Music

At some point, well into the night, maybe an hour or two before sunrise, I heard celestial music. I opened my eyes and saw nothing but darkness. I asked myself where I was but couldn’t recall. I became dimly conscious of soft harmonies. It wasn’t just music alone but angels singing too — tender, lovely voices — highs and lows blending and melting into each other. I closed my eyes, and nothing changed — complete blackness and music from heaven. I opened my eyes, groped in the night for Oscar’s hand, found it, and asked, “Do you hear what I hear?”

“Yeah,” he said in a hushed voice, “Where are we?”

“I think we’re dead but in a good place.” I told him.

I tried to look out our window but could see nothing in the morning darkness. We lay for a long while without a word until, at some point, one sole bird, and soon many joined the chorus.

A few minutes later, we saw a tiny light beginning to warm the sky. As dawn came, we stood at our window and looked at the virgin morning. We now saw what we hadn’t last night — our room faced the back of the hotel overlooking a sports field. These memories always linger. I gazed upon hundreds of Fiji’s true believers scattered into a dozen or more groups in a circle around the rugby field. Each church choir cluster wore a different color — looking towards six o’clock, there were ladies in mint green dresses, eight o’clock a mixed group, the men in pale blue shirts and sulus — traditional Fijian men’s skirts, the women in dresses the same shade of blue, nine o’clock coral dresses, and so on, all combining into a majestic shining circle of pastel-rainbow colors growing ever more vibrant as the passing minutes moved the sun upward.

|

|

Sunrise in Levuka.

|

And they sang. And they sang. Each gathering would initiate a song or hymn, and as they approached the climax, another would chime in with their own. At that moment, I felt a profound sense of awe, as if I was on the threshold of heaven. The breakfast revelation was equally astonishing — the annual Methodist convention, including a choir competition, was scheduled for that evening. These devoted disciples would practice tirelessly all day, their harmonies never ceasing. If this was practice, I could only imagine the celestial beauty of the actual competition.

Wherever we ventured that day, the air was filled with song — on the sun-kissed beach, as we ascended the renowned one-hundred steps into the hills to admire the breathtaking bay, and even out at sea. The details of our day may have faded, but the memory of the singing remains vivid — a constant, melodic backdrop that became an integral part of our being, permeating our very essence.

Finally, after a full day of sightseeing, we headed back to our charming nineteenth-century hotel room. I fell asleep early, still surrounded by heavenly harmonies, blissful and contented. Much later, deep into sleep, I jerked awake. Something had happened. Something had awoken me. Something was amiss.

“Oscar!” I whispered, feeling anxious and frantic. Something’s wrong. What’s happened?”

“It’s OK, love,” he whispered back. “The music just stopped. The competition’s over.” And we drifted back to earthly dreams.

A Human Resources consultant who loves living internationally, Susan Bonetto has lived in Fiji twice and the Philippines once and currently resides part-time in Argentina. She has also traveled to over 30 countries for pleasure or work. Susan can be contacted at scbonetto AT yahoo.com

|